Across the world, mosquitoes are quietly redrawing the map of infectious disease, and Nigeria is no exception. The growing encroachment of invasive Aedes mosquitoes, driven by globalisation, urbanisation, climate change, and increased movement of people and goods, is fuelling the spread of deadly viruses like dengue, chikungunya, yellow fever, and Zika.

Mosquitoes Behind the Outbreaks

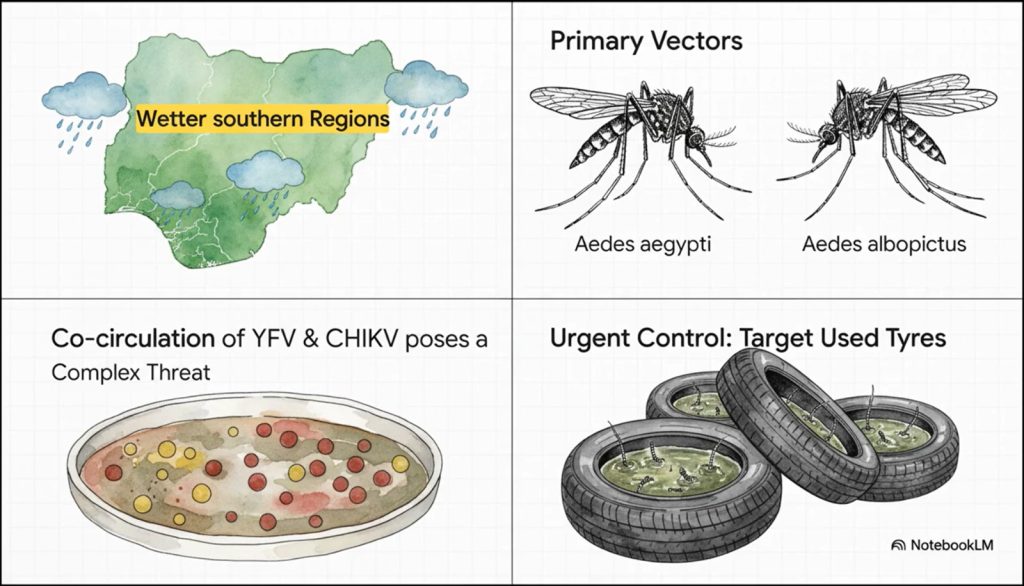

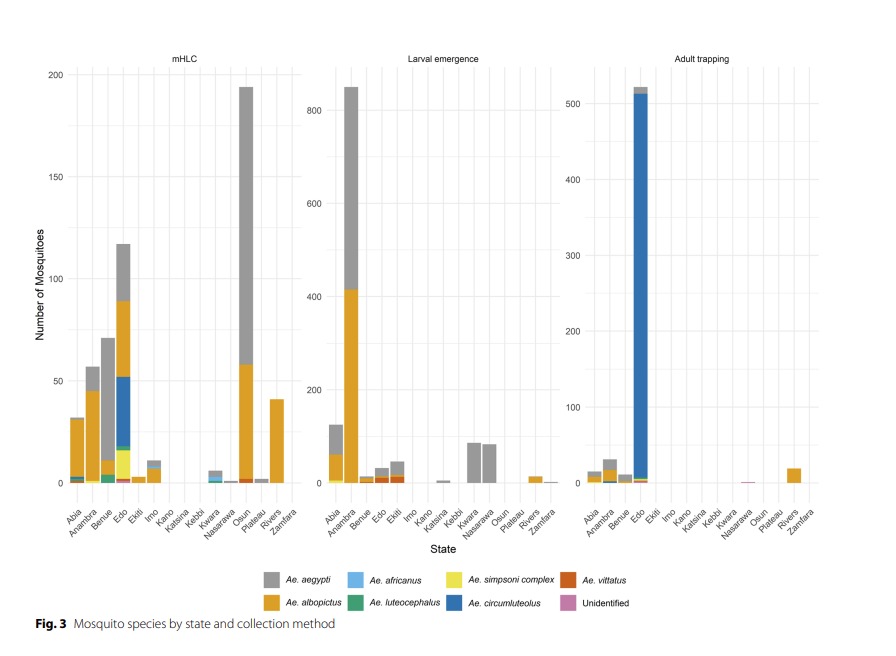

Two species stand out as the main culprits: Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Both are efficient carriers of several arboviruses and are increasingly found across Nigeria’s ecological zones, from the coastal rainforests to the arid savannas. But they are not alone. Other Aedes species, such as Ae. africanus and Ae. luteocephalus also contribute to transmission, particularly in rural Africa, where outbreaks often begin unnoticed.

A Silent Crisis: Gaps in Funding and Diagnostics

Despite the rising threat, Africa remains underprepared. WHO reports highlight a critical lack of funding, technical support, emergency resources, and trained personnel for arbovirus control. In Nigeria, diagnostic capacity for diseases like dengue and yellow fever remains extremely limited. Without better surveillance tools and a deeper understanding of local mosquito behaviour, outbreaks will continue to catch health systems off guard.

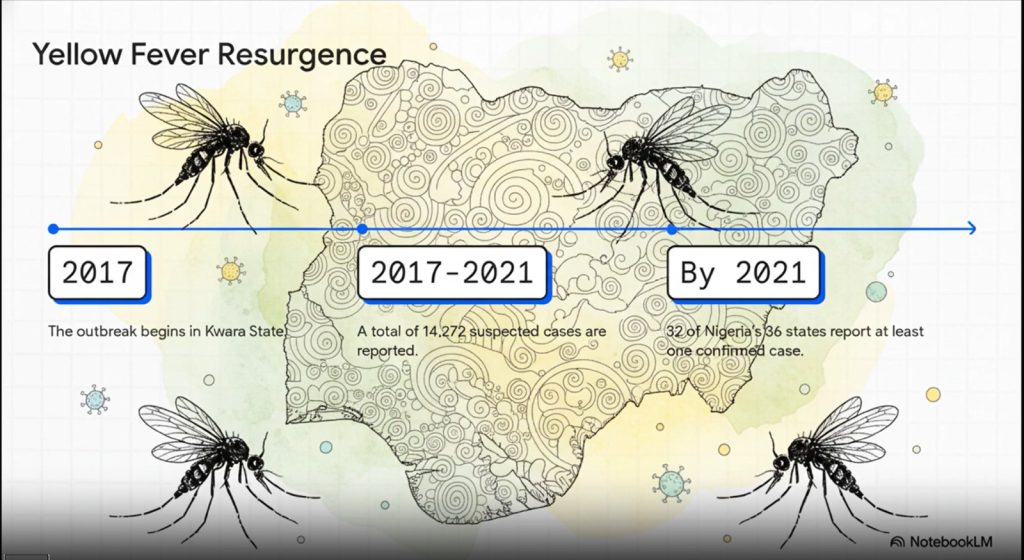

Yellow Fever’s Resurgence in Nigeria

Yellow fever, once thought to be under control, has made a troubling comeback since 2017. Outbreaks have been reported in multiple states, often in rural communities where people live and work close to forested areas inhabited by infected non-human primates and sylvatic Aedes mosquitoes. The overlap of yellow fever with other arboviral infections poses a severe public health challenge and calls for an urgent, coordinated response.

Inside the Study: Understanding the Mosquito Landscape

Researchers surveyed 57 local government areas across 16 Nigerian states, focusing on rural regions where agriculture dominates. The study spanned Nigeria’s diverse climates, from the humid, rain-soaked coasts to the dry Sahel, allowing scientists to examine how weather patterns and ecosystems shape mosquito populations and disease risks.

Through larval surveys, human landing catches, and specialised mosquito traps, over 2,400 Aedes mosquitoes were collected and analysed. The team identified seven distinct species, showing a clear trend: mosquito richness increases from the dry north to the wetter south.

Where the Threat Breeds

Household water containers, discarded tyres, and earthen pots emerged as the most common mosquito breeding sites. In northern Nigeria, earthen pots and tyres dominated, while in the south, used tyres and discarded containers were hotspots. In most states, indices such as the Breteau and House Indices far exceeded WHO’s epidemic risk thresholds, clear evidence of widespread vulnerability to arboviral transmission.

Viruses in the Mosquitoes

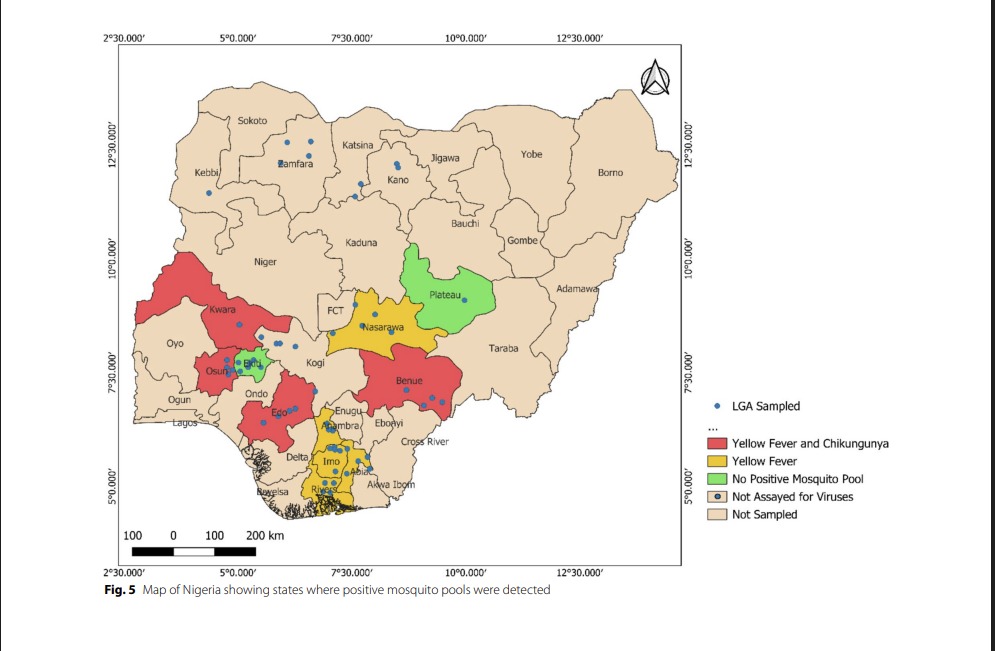

Laboratory testing confirmed the presence of yellow fever virus (YFV) and chikungunya virus (CHIKV) in mosquito pools from 11 Nigerian states. Dengue, Zika, o’nyong’nyong, and West Nile viruses were not detected during this survey.

- Yellow Fever Virus: Found predominantly in southern states, with Edo recording the highest infection prevalence (64%).

- Chikungunya Virus: Detected in Kwara, Edo, Osun, and Benue, with infection rates varying by region and species.

Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus were the primary carriers of both viruses, confirming their critical role in Nigeria’s arbovirus transmission cycle.

Evidence of Vertical Transmission

The study uncovered alarming evidence that some mosquitoes can transmit the yellow fever virus directly to their offspring. This means the virus can persist in mosquito populations even when no human infections are present, making eradication significantly harder.

What the Findings Mean

The research paints a clear picture: Nigeria faces a persistent and evolving risk of yellow fever and chikungunya outbreaks. High mosquito densities, widespread breeding habitats, and low vaccination coverage have created a perfect storm for arbovirus resurgence.

The wetter southern regions are especially vulnerable due to higher mosquito diversity and infection rates. The coexistence of YFV and CHIKV in mosquito pools suggests that multiple viruses may be circulating simultaneously, increasing the risk of co-infections and complex outbreaks.

Why This Matters and What Must Be Done

This study should serve as a wake-up call for public health authorities, policymakers, and international partners. The fight against arboviral diseases in Nigeria cannot rely on reactive measures alone. It demands:

- Stronger entomological surveillance to monitor mosquito populations and detect viruses early.

- Sustained funding and local capacity building for diagnostics, training, and rapid response systems.

- Environmental management to eliminate breeding habitats, especially in urban and peri-urban areas.

- Expanded vaccination coverage for yellow fever and community engagement to ensure participation.

The evidence is clear: the mosquitoes are adapting faster than our control measures. Without urgent investment in science, surveillance, and prevention, arboviruses will continue to spread, turning preventable diseases into recurring national crises.

Read full Article here: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13071-025-07051-z?utm_source=rct_congratemailt&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=oa_20251031&utm_content=10.1186%2Fs13071-025-07051-z